“The difference between successful people and very successful people is that very successful people say “no” to almost everything.”

Warren Buffett

Getting locked in on your priorities sounds empowering until you realize what it actually means: being deliberately terrible at everything else.

Your friend who’s absolutely crushing it at work? Their car is a mobile storage unit for coffee cups and gym clothes. They’ve survived on takeout for six months straight. They couldn’t tell you their nephew’s age to save their life.

They’re not struggling with time management. They’ve just done the math that the rest of us avoid.

After years of cultural whiplash—from hustle culture’s “do everything” to soft life’s “rest from everything”—we’ve stumbled into something more honest.

The Great Lock In movement of 2025 captured it perfectly: 121 days of people choosing their battles and documenting the peace that came from finally letting everything else go.

This isn’t another productivity trend. It’s permission to stop performing a capability you don’t actually have.

Let’s trace how we got here, because the journey matters.

Hustle culture told us to be exceptional at everything. Career and fitness and relationships and side hustles and personal growth and networking and hobbies and financial literacy. The message was clear: if you’re not optimizing every domain, you’re losing.

We tried. God, we tried.

The result? A generation of people having panic attacks in their cars before work. Therapy waitlists stretching months. Everyone was exhausted, and nobody wanted to admit they were barely holding it together.

Then came the soft life backlash. Rest! Boundaries! Stop grinding! The pendulum swung hard in the opposite direction.

It felt revolutionary at first. Permission to not hustle felt like oxygen after drowning.

But ambition didn’t disappear. People still wanted to build things. Was wanting excellence automatically toxic? Was ambition just capitalism wearing a cute outfit?

Enter being locked in. Not hustle culture rebranded. Not soft life’s cousin. Something different entirely.

It’s the synthesis we needed: you can pursue extraordinary outcomes. Just not in every domain simultaneously. You get to choose your peaks. Everything else can be valleys, and that’s not failure—that’s geometry.

This realization crosses generations. Boomers burned out chasing “have it all.” Gen X quietly gave up on certain fronts years ago. Millennials do it while feeling guilty about it. posts TikToks about what they’re not doing.

The conversation is shifting. We’re finally admitting what high achievers have always known: excellence requires trade-offs, and pretending otherwise makes you exhausted and mediocre.

Here’s what nobody wants to tell you: the people we celebrate for their accomplishments were often disasters everywhere else.

Leonardo da Vinci left tons of projects unfinished. Einstein’s personal life was chaotic, and his relationships suffered. Darwin was a social recluse who barely left his house.

They weren’t well-rounded. They were incredibly spiky—sharp peaks in their chosen domains and deep valleys everywhere else.

We’ve been sold a fantasy. The Renaissance polymath who excelled at art, science, engineering, and philosophy, and probably made excellent pasta on the side.

Basically, the 1500s version of an influencer who claims they run six businesses, meditate for two hours, and still have time to rescue stray cats on YouTube. It’s a nice story. It’s also largely fiction.

Modern social media amplified this delusion to absurd levels. Your college roommate posting perfect gym-career-travel-relationship content—is even more fictional.

What you don’t see: they’re locked in on two of those things. One is probably their job paying for it. The rest is performance art, outsourcing, or free-falling behind the scenes.

The science backs this up. Research on decision fatigue shows we have finite cognitive resources. Studies suggest the average person makes about 35,000 decisions per day, and decision quality deteriorates as mental resources deplete.

Mastery requires deliberate practice. Deliberate practice requires time. Time is the one resource you can’t optimize your way out of.

This isn’t motivational—it’s mathematics. Twenty-four hours in a day. Seven days in a week. If you want mastery-level outcomes in anything, something else has to give.

The question isn’t if you’ll make trade-offs. It’s whether you’ll make them consciously or feel guilty while pretending you’re not.

Being locked in isn’t just about focus—it’s about active, guilt-free neglect of everything else.

Here’s the framework nobody wants to say out loud: You get to be excellent at 2-3 things. Competent at a handful. Mediocre at the rest.

That’s not failure. That’s honesty.

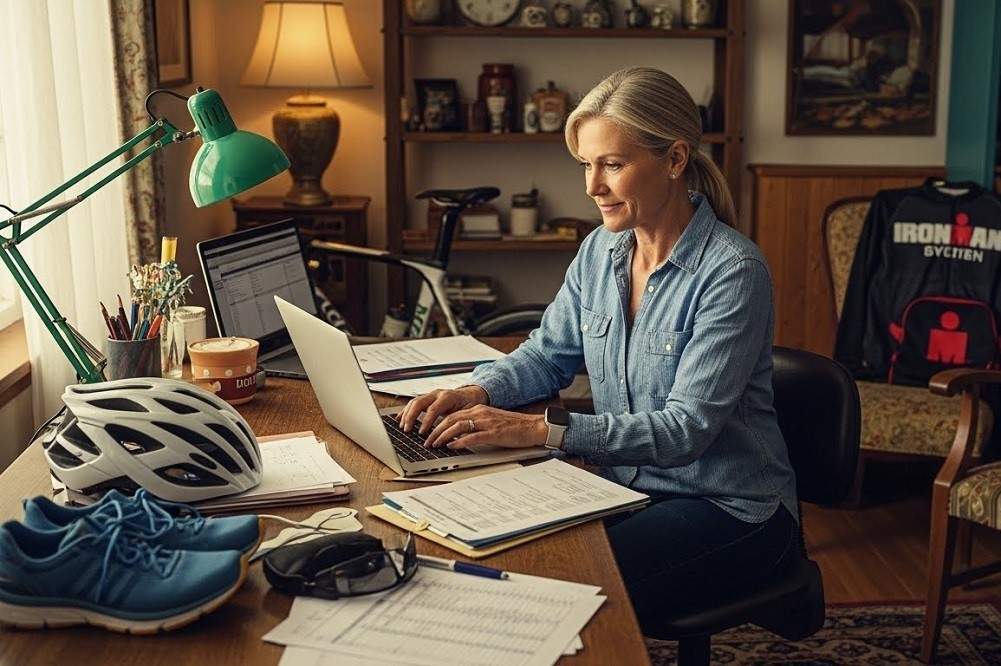

Meet Sarah, 54, locked in on reaching VP and training for an Ironman. She hasn’t read a novel in seven years and decorates her home with whatever was on sale at the time she needed it. No guilt. These are the trade-offs for the peaks she picked.

Meet James, 29, locked in on writing and deep friendships. His career is a paycheck. His plants die regularly. He’s publishing a novel before 35 and doesn’t care about his 401k alphabet soup.

Meet Lin, 43, locked in her kids and community organizing. Career ambition? Paused. Fitness? Nonexistent. Hobbies? Later. Maybe.

Meet Robert, 67, locked in on grandparenting and painting. Current events? Someone else’s problem. House maintenance is now “hire someone or live with it.” He’s never been happier.

The pattern is clear. None of these people are failures. They’re just honest about their math.

Trying to be great at everything means being mediocre at everything. It’s like trying to learn five languages at once—you end up ordering bad coffee in all five.

Being locked in feels difficult because we were raised to feel guilty about conscious neglect. Parents said, “You can be anything you want!” Teachers reinforced it. Society nodded along.

What they didn’t mention: “…but not everything you want, simultaneously, without brutal trade-offs.”

The privilege piece is real. Not everyone gets to choose their mediocrity, and that matters. Single parents can’t choose to be mediocre at childcare. People in economic precarity can’t coast at their day jobs. Caregivers can’t deprioritize family obligations.

The ability to choose where you’re mediocre is itself a form of privilege.

But even within constraints, there’s more choice than we think. The question isn’t “Can I neglect all responsibilities?” It’s “Within what I must do, what do I want to do deeply versus adequately?”

Example: The single parent working full-time might still choose to be locked in on building one deep friendship and reading to their kids every night. Everything else—cleaning standards, PTA involvement, personal appearance, social obligations—can be just okay.

That’s still a choice. That’s still selective excellence within constraints.

Generational guilt patterns are fascinating. Boomers are deeply uncomfortable admitting they’re not trying at something—it feels like weakness. Gen X does it quietly and never discusses it. Millennials do it while feeling guilty and over-explaining to everyone. Gen Z posts Instagram stories about what they’re deliberately not doing.

Different approaches. Same underlying reality. Everyone’s making trade-offs. The only variable is how much guilt you’re carrying about it.

Research on life satisfaction consistently shows that depth beats breadth. Being exceptional at a few things feels better than being mediocre at everything.

This isn’t a “5 steps to find your passion” framework. Those are useless, and you know it. Instead, try these diagnostic questions. They’re uncomfortable. That’s the point.

The seasonal approach matters. Being locked in isn’t a life sentence. You might be locked in on different things at 25, 45, and 65. People change. Priorities shift. This is normal, not flaky.

Red flags you’ve chosen wrong:

Green light—you’ve chosen right:

Choose based on green lights, not what looks good from the outside.

Being locked in requires constant small acts of disappointing people.

The graceful decline is an art form.

“I’m not doing that right now” becomes a life skill. No TED Talk required. “That’s not a priority for me” is a complete sentence. Use it liberally.

Managing relationships when priorities don’t align takes honesty. If your partner is locked in on fitness and career while you’re locked in on creativity and friendships, you’re not incompatible—you’re climbing different mountains. Just say so out loud.

Generational approaches to this vary wildly. Older generations quietly deprioritize but maintain appearances—nobody discusses what’s being neglected. Younger generations openly declare what they’re not doing, sometimes performatively.

Both approaches work. Pick your style based on your personality, not your birth year.

There’s something counter-cultural about strategic mediocrity. We’re swimming in a culture that screams “optimize everything!” Every productivity guru wants to help you level up ALL areas of your life simultaneously.

But what if most areas of your life being unremarkable is… totally fine? What if adequate is genuinely adequate?

We’ve reached peak absurdity. There are YouTube tutorials on the optimal way to load a dishwasher. Unless you’re competing in the Dishwasher Loading Olympics, adequate is fine. Your dishes will get clean either way.

Being locked in means refusing the pressure to optimize domains that don’t matter to you. It is a rebellion disguised as apathy.

The monk mode crowd (which we’ll explore separately) takes this even further—eliminating distractions entirely for deep focus periods. But that’s about technique. This is about permission.

The Great Lock In resonated because it gave people something they desperately needed: permission.

Not permission to be lazy. Permission to stop pretending. Permission to be brilliant at some things and genuinely mediocre at others.

It wasn’t just a 121-day challenge. It revealed what people actually want—to choose their battles without guilt.

We lived through the full sequence: hustle (do it all), soft life (do less), and now locked in (choose your peaks). Monk mode is the technique layered on top when you’re ready to go deep.

The person who’s exceptional in 2–3 domains and mediocre in the rest hasn’t failed. They just figured out how reality works.

Excellence requires trade-offs. Mastery requires time. Humans are finite. The only real choice is whether you’ll make those trade-offs consciously.

Pick your peaks. Choose 2–3 domains where you want to be exceptional. Invest unapologetically.

Let everything else be adequately mediocre. Your laundry can be wrinkled. Your Netflix queue can remain unwatched. Your houseplants can die.

Sleep well knowing you’re excellent where it counts to you.

The Great Lock In gave us permission to admit this out loud.

Now the rest is up to you.

DISCLOSURE: In my article, I’ve mentioned a few products and services, all in a valiant attempt to turbocharge your life. Some of them are affiliate links. This is basically my not-so-secret way of saying, “Hey, be a superhero and click on these links.” When you joyfully tap and spend, I’ll be showered with some shiny coins, and the best part? It won’t cost you an extra dime, not even a single chocolate chip. Your kind support through these affiliate escapades ensures I can keep publishing these useful (and did I mention free?) articles for you in the future.

READ NEXT